I am in Altenessen and am sitting in the bright room belonging to the project MifriN. Photos and posters of activities and offers are hanging on the walls: the games bin, school mediators, counselling. MifriN stands for Migrants in a Peaceful Neighbourhood. Ramadan, one of the social workers, offers me something to drink. Standing in front of me on the table, there are a bottle of water and a bottle of cockta, a drink I know from my last trip to the Balkans. Ramadan pours me a drink and I thank him for translating for me today. After a short while, Isabela enters the building, together with her mother and a stroller. Isabela and I have only seen each other once very briefly so far, when I picked up the camera. Now she’s sitting down between Ramadan and me while her mother lifts the baby out of the stroller and carries it around the room in her arms.

Before I take out the pictures, I ask how it was for her to take the pictures. „She liked it a lot. She felt quite comfortable doing it,“ Ramadan translates. I show Isabela the first photo: it is a picture of her, here in the building. She laughs and covers her face with her hands. I ask her who took the picture. She points to her mother and holds the photo out to her. She looks at it and smiles. I ask if the two are living together. No, Isabela explains, they don’t live in the same flat, but in the same street. Isabela lives alone with her daughter. I ask her about the baby. It is her first child and just seven months old. What is it like for her to be a mother? „It is a very nice experience for her,“ Ramadan translates, before quoting her directly: „Even when she cries, I like to take care of her. I give her food and stuff all the time.“ I ask her if her mother helps her a lot with the child. „If help is needed, she does it,“ Ramadan translates. I ask about the child’s father. „He doesn’t take care of the child. He saw it, but he doesn’t want any contact with the child.“ – „Too bad,“ I say. Isabela shrugs and makes a gesture with her hand. „Good alone,“ she says and smiles gently.

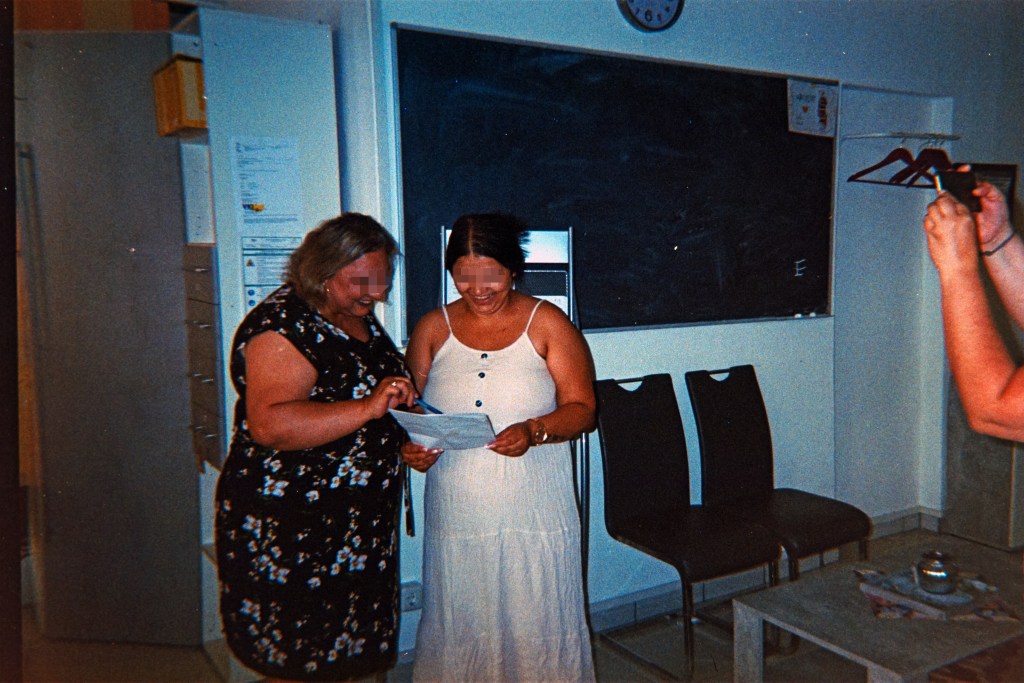

I show her the next picture. „This is my mother,“ she says. This photo was also taken here. The woman next to her is her mother’s sister, Isabela explains. I ask her if they come here often. „Yes.” How does she know the place, I ask. They know about the project through other people around them. „They come here to do things. Paperworks and stuff,“ Ramadan translates.

I look at Isabela and ask her: „You understand German, don’t you?“ – „Yes,“ she nods. I ask her if she has taken a German course. Again, she nods. How long has she lived in Germany? She looks over at her mother and asks her. „July 2016,“ Ramadan translates. She was 14 years old at the time. I ask where she lived before. The family came to Germany from Romania, but had previously lived in Italy. Why did they come to Germany, I ask now. „In Romania, because they are Roma, she was always hindered in her life. She was never allowed to go to school in Romania, she was not allowed to work, and if she did, she worked below the minimum wage. Exploited all the time. And she feels more comfortable in Germany.“ I ask Isabela if she went to school here in Germany. „Yes,“ she answers. „What was it like for you?“, I ask. „In the beginning it was difficult because she had no one, no friends,“ Ramadan translates her answer. „But after a few weeks, when she had built up a circle of friends, it was fine.“ I ask if she is still friends with her former classmates. „With various ones. Not all of them, but a few. Two, three, four.“ What language do they speak among each other? „One speaks only German and the others are Romanian.“ She speaks German with the German friend, she says.

When I ask Isabela how long she went to school, she looks back over at her mother, who is bobbing the baby up and down slightly. The two women are thinking about it simultaneously. Three, four years, she says now. We talk about what she would like to do for a living. „She would like to be a hair stylist, she enjoys that. But she’s not sure yet, she could still change her mind.“

I show her the next picture and ask who the people in the photo are. She is with her sister’s daughter and a friend of her mother, Isabela explains. The picture shows the three of them in the city centre. Does she go there often, I ask. „Yes, for a walk. From Essen main station,“ she says. I ask what else she likes to do in her spare time. „When she’s not talking a walk in the city centre, she’s looking after her baby or cooking at home or shopping groceries,“ Ramadan says. „Cleaning,“ adds Isabela. We talk about what she likes to do, what she enjoys. „She used to love playing football, but now she can’t.“ Did she play in a team? „She didn’t make it, unfortunately. She always wanted to, but didn’t make it.“ – „And now because of the child she can’t continue?“, I ask. „She isn’t feeling it anymore. Now I prefer to take care of my child,“ Ramadan translates. „Does she feel that her life has changed a lot since the child? „, I ask now. „Yes, very much! But in a positive way,“ he says. „Good, good!“ adds Isabela, beaming. I ask what her child’s name is. „Erika, is German name,“ she says with a smile. How did she come up with the name? She answers Ramadan, then looks at me, holds up her mobile phone and says: „Google“. Two weeks before the birth, she finds the name on the internet. „And who is Eva?“ I ask, pointing to the tattoo on her forearm – the name framed by two stars – which I had noticed before. She pulls one of the photos we’ve already looked at out of the pile and holds it out to me: „Eva!“ It’s her sister’s daughter. The next picture I put in front of her also shows her niece. „Eva, play.“ Eva is six and has recently started school.

I show Isabela the next photo. She laughs. Who is this, I ask. „That’s my dad, my mother and my mother’s friend.“ I turn over the next one: a photo of her eldest sister in her flat. Do they spend a lot of time together? „Every two or three days they are together.“ She has three siblings, Isabela continues. The two younger siblings still live with their parents; Isabela and her older sister live alone.

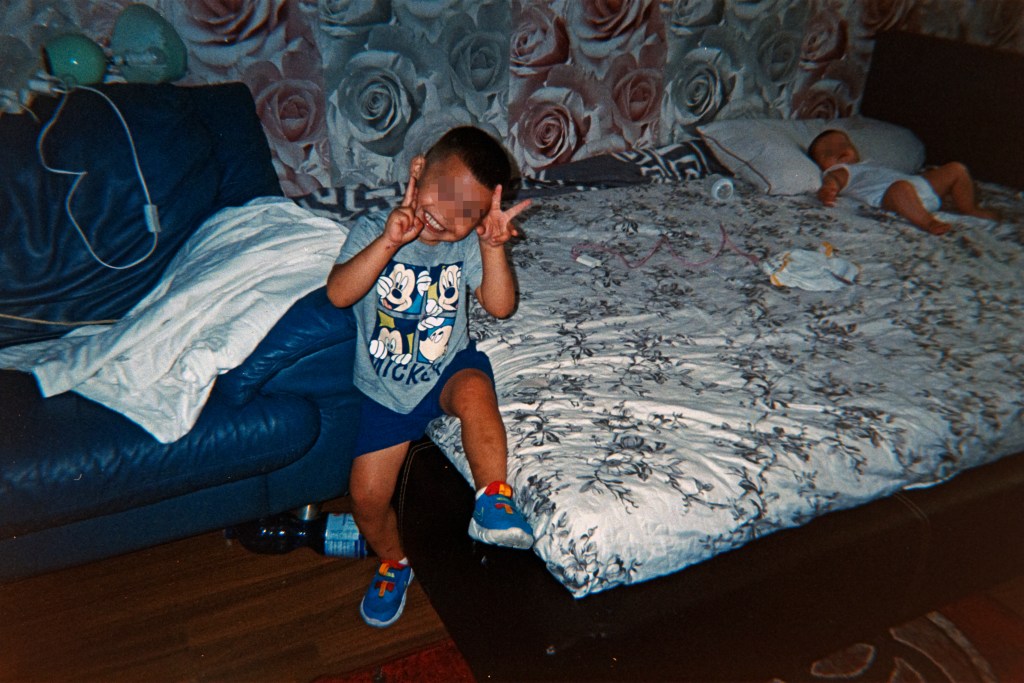

Another picture of Eva, followed by a photo showing Eva’s little brother. „Nikki“, Isabela explains.

When I put the next picture in front of her, she’s beaming again. It shows Erika’s crib. I ask her if she wants more children. „No,“ she answers firmly. „One is good.“

The next photo shows a mattress and a blanket. Isabela takes the picture in her hand and looks puzzled. She shows it to her mother and laughs. „That was Nikki.“ Six times in a row he takes a photo of the same subject: the mattress. We laugh out loud and Isabela shakes her head: „Kids… sorry!“

The next photo shows her again in the room belonging to MifriN. „Child support, family benefits office,“ she says. Ramadan adds that in the picture, she has just been assisted filling out documents for Erika’s child benefit. It’s all working out, everything’s fine, she says. I ask if she already knows when she wants to go back to work or school, or if she will stay at home indefinitely for now. „No, I need school! Because I don’t understand German so well.“ – „When Erika is a bit older, she wants to start again,“ Ramadan continues to translate.

We talk about how she’s doing in Essen in general. Does she feel comfortable? „She likes it here a lot, she’s already settled in.“ And what does she want for her future? How does she imagine her life in ten, fifteen years? „She still sees herself in Germany, that she will definitely stay here. But she doesn’t know any other than that yet. But I’m definitely not going back to Romania. „She looks at me emphatically while Ramadan translates. We talk about the time before she came to Germany. „She was born in Romania, lived there until she was eight. But then her parents kept taking her to Italy.“ Until she is twelve. Then she returns to Romania with the family to prepare the emigration to Germany: Getting papers, identity documents. „Why Italy?“ I ask. Isabela’s mother explains to Ramadan that her parents worked in Italy. Actually, the work was only supposed to be temporary and the children were therefore supposed to stay in Romania. When it turned into long-term work, they bring the children to live in Italy with them. „And how was it in Italy? „I ask Isabela and her mother. „It was very nice,“ Ramadan translates what Isabela says. „It was close to the sea, the summers were very nice. She liked it very much.“ – „Mare,“ the mother says and smiles.

Did the parents always live in Romania before they went to Italy? „Only in Romania,“ Ramadan translates what the mother says. I ask if it was that bad for the parents back then too, if they were also denied access to education and work. While her mother answers, Isabela takes Erika in her arms. She presses the laughing baby to her face, kisses and rocks her. The mother, who now has her hands free, gesticulates a lot while talking. Every now and then she looks at me with her alert gaze and I have the feeling that I understand something. Ramadan starts to translate again. „It was a bit bad, but it wasn’t as bad before as it is now. Today you can’t live there as a Roma because you are immediately racially attacked. That’s why we left altogether as a family then.“ – „And what would she say was the reason that it got worse?“, I ask. „Because of the politics. The discrimination.“ – „Does she sometimes miss Romania? Or do the negative experiences outweigh that?“ When she answers, she presses her hand to her chest. „She, yes. Some nostalgia is there. But because of the children, who don’t want to go back there, she stays here. I can’t do anything, I grew up there and was born there. But it’s not just up to me.“ She looks at me, points to her daughter holding her grandchild and says in German, „Children, school, everything!“ She shrugs her shoulders, looking tired. Does she feel comfortable in Germany? „She likes Germany very much, too. I don’t have to worry about anything, I’m helped with everything here. I am not abandoned here. From that point of view, everything is good.“ While Ramadan translates, Isabela’s mother takes the baby again and carries it bobbing around the room. It beams over at me and we look at each other. Isabela says something to Ramadan and looks at me expectantly as he translates, „She says Erika doesn’t often smile at strangers.“ I am genuinely touched and smile at Isabela and her daughter.

When we come to the end of the interview, Isabela asks if I take all the pictures with me. I explain that I need the pictures for the project and ask her if I should make copies for her. She takes the stack, looks for pictures and lays them out for me: a photo of Erika, one of her mother and Eva; Isabela with Erika in her arms at MifriN. We fill out the data protection form together and I explain again how the project will proceed. After Ramadan has translated everything, I ask if Isabela has any questions. She nods and answers him. „When will she get the copies of the pictures she chose? She would like to have them for her home.“

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar