The first time I speak to X is on the phone. He has my number from someone I told about the project. He calls to tell me that he would like to take part. We have a brief exchange, meet a few days later in a shopping centre in the Ruhr area. Our second meeting is at a train station in another city. Now we are sitting in the shade of a park on a hot day, on our left a woman is having breakfast on a bench, on our right two young men are dealing in a pavilion.

I ask X if it was easy for him to find subjects to photograph. „Whenever I did something that I would have posted on Instagram, I photographed it with the camera,“ he says with a laugh. Fittingly, the first photo I put between us shows a table with food and drinks. That was at Café Extrablatt, he tells me, together with a fellow student. I ask him what he is studying: Japanese and economics. He started learning Japanese even before his Abitur and now speaks the language on B2 level. „But I didn’t want to do solely Japanese studies, because that’s just very culture-related, and somehow I also wanted to do economics.“ So he did some research and found his current degree programme. He started his studies in the middle of the pandemic, the first semester was completely online. I ask him what it was like for him to start like that. „Yes, it was difficult. It wasn’t difficult concerning the contents, because I understood the things anyway. It was just difficult because I’m very shy and couldn’t get to know people, that was the worst.“ By now, however – since he has been able to attend university physically – his situation has improved. „It’s just that when I’m somehow put into a group, it’s no problem for me to meet people, but when I’m in my room, alone, and there’s no possibility of meeting people because everything is online, then I can’t do that at all. But now it’s changed for the better.“ I ask X if he still has friends from school. „No, not at all, because I went to school in Tunisia. And I don’t have any contact there anymore.“ He tells me that he came to Germany after his Abitur and first went to the Studienkolleg in Tübingen for a year to get his entrance qualification for university. „So you’re not from the Ruhr area either?“ – „No.“ – „Were you born in Tunisia too?“, I ask. „Yes. But my mum is German, so I can speak German too. And I went to kindergarten in Germany, though, and I did my schooling in Tunisia.“ X’s mother comes from a village near the Dutch border. His parents met in Tunisia and lived together in Germany for several years before he was born. „And what was it like for you growing up in Tunisia?“ – „It had advantages and disadvantages. Advantages were: You learn more languages in Tunisia, you … – I don’t know, it’s just a beautiful country, one way or another. And when you grow up in two cultures, I think there are actually more advantages to growing up in Tunisia than in Germany. What was a bit difficult, of course, is that homosexuality is forbidden in Tunisia, and I like men. That was a bit difficult.“ I ask if he has come out to his family. „Hm, to my mum, yes. My dad died in 2017, and two months later – but that was not related to it – I told my mum. But I didn’t tell anyone else in Tunisia.“ – „So you’ve never had a boyfriend or anything in Tunisia?“ – „For God’s sake! If you do – you can go to jail!“ – „So you don’t even know how the community lives there? Because I mean, there are queer people in Tunisia.“ – „Yes, there are. And they live very hidden. And they don’t live openly. You get the impression that there are only straight people there. And there are certainly gay/lesbian people who pretend and enter heterosexual marriages because the pressure from the family, society and so on is too strong.“ I ask if that was one of the reasons why he went back to Germany. No, his homosexuality was not the main reason, X explains, either way he would have come to Germany to study here. His mother also went back to Germany, a year after he moved here. He has no brothers or sisters. „So now there’s not really that much that still connects you to the country?“, I ask. „Yes, unfortunately. My dad had a family, but my mum had a falling out with them.“ He can’t imagine going back at the moment. I ask X what his relationship with his father was like. „It was quite … okay,“ he says carefully, „well … mediocre,“ he laughs softly. „It wasn’t the best, but yes, it was okay.“

He has now been living in Germany for three years. I ask him if he feels comfortable here, in the Ruhr area. „Well, I feel good in Germany. In the Ruhr area… on the one hand, yes, because I have very good friends here and people I can do things with and so on. But on the other hand – this is going to sound racist – there’s a very high percentage of migrants with a Muslim background in the Ruhr area, and since I grew up in a Muslim country, I know how homophobic people are. And that’s why I feel a bit uncomfortable.“ – “Has that also happened to you, that you were somehow assaulted here in Germany?” – „Nah, it hasn’t happened because I always keep my mouth shut,“ he laughs. „And also, I only come out to friends where I know it’s not a problem.“ I ask if since he’s been back living in Germany, X has had a relationship, which he shows publicly. „No, I haven’t had one yet. But if I had a boyfriend, I wouldn’t want to hide it or anything.“ – „But would you be afraid to walk through the city holding hands with your partner?“ – „Yes, I wouldn’t do that in the Ruhr area. Maybe in Tübingen. I don’t know if you know Tübingen, it’s kind of stuck up. I’d dare to do it there, but not here.“ He’s thinking about it. „And even in Tübingen I wouldn’t do it one hundred percent.“ – „Can you think of any place where that would be okay? Where you’d really feel one hundred percent comfortable and not think about it?“ – „Yes, on a beach where there are no people.“

We talk about X’s group of friends, about the people in his life. „My fellow students are my biggest circle of friends. Besides them, I have friends I met on dating apps who are also gay, but I’m just friends with them. There are two good friends near here. Then I have another good friend from the Queer of Colour Group. Yeah, that’s it actually.“ I ask him how he came across the group. „I was in a support group for students with depression. And I asked them if there was any group for queer people, and they gave me the contact.“ He no longer goes to the support group. „The thing is, I was very depressed when I was very lonely because of covid. And because that has subsided and I’ve been able to get to know people again because of the relaxation of the restrictions, I don’t need them now, and I’ve also had a psychotherapist for a year now. And the group has become quite anyway, no one came there anymore.“ He sees the therapist regularly and she has just applied for long-term therapy for him. I ask him if he feels that the therapy is helping him. „The therapy … yep.“ – „Not so much?“ – „Well, I have to do everything myself in the end. But it does help if you have a therapist in the background with whom you can talk, who is also neutral, that does help, yes.“ – “Do you have the feeling that you have people around you with whom you can talk openly about problems and such?” – „Yes, I can talk well with friends.“ I ask X about his contact and relationship with his mother. „Well, we talk on the phone about two or three times a week on average, for twenty minutes, just exchange news. Yes, that’s really it. And I visit her three or four times a year, always for a week. „She has also settled back in in Germany and has gone back to the town where X used to go to kindergarten.

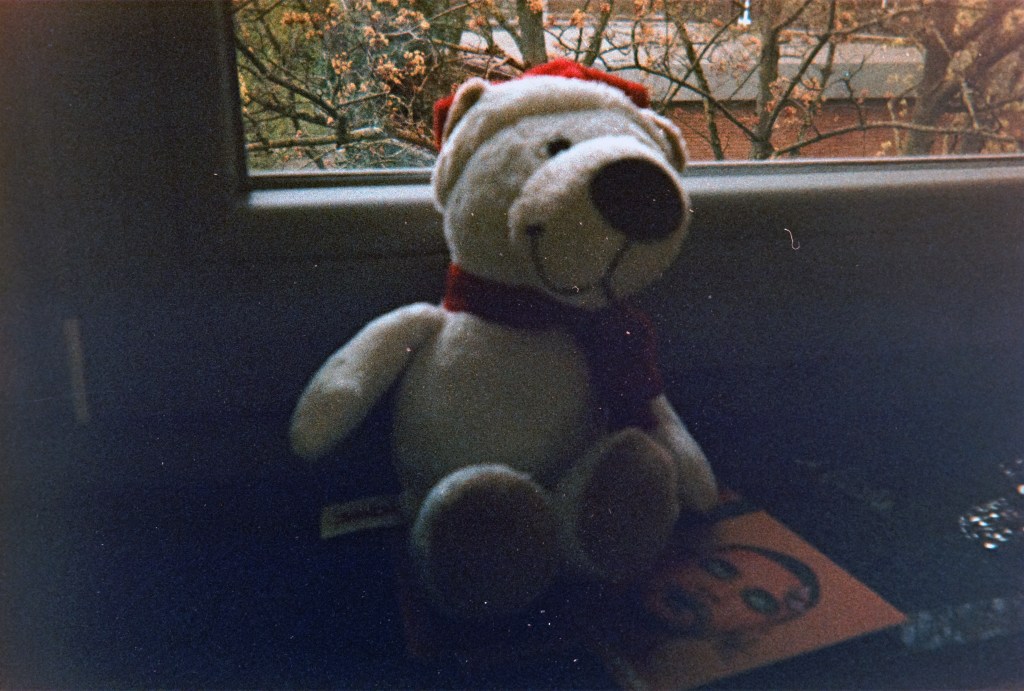

The next photo I put between us shows his student dormitory, the view from his window. How does he like living there? „Not so much. Well, the dormitory is modern. Luckily, I have a single flat. But I lived with two guys at the beginning, one was from Egypt, one from … Lebanon, I think. In any case, they were both religious. That brings us back to the homophobia issue. I didn’t have to ask them if they were homophobic, I just knew because I grew up with people like that. And I didn’t want to feel uncomfortable if I had a boyfriend and brought him home or something like that. That’s why I really wanted to get out of there. And I kept complaining until I got a single flat two months later, where I’ve been living for over three semesters now.“

We continue talking about X’s life and his experiences in Tunisia and I ask him what his group of friends was like there. „I didn’t really have many friends in Tunisia, to be honest. I only ever had a few. At school – it depended on the school year, because the classes were always mixed anew every year – in some school years I had more people with whom I got along, in some I didn’t. In my free time I hardly met anyone.“ He continues: „My everyday life in Tunisia was very unspectacular. I went to school, we have very long school days, from eight to six, with a lunch break in between. I had school, language school, and sometimes I went to do sports. When I was a child, I played a lot with people in the street, that’s very common there. When I got older, from about 14 or 15, I tended to isolate myself.“ – „Can you tell me why that was?“, I ask. „Well, I made much better friends with girls than with boys in Tunisia. Because there was a kind of toxic masculinity there, and I’m not that type at all. I made more friends with girls, but in Tunisia it’s not really usual for a girl to hang out with a boy. That’s probably why. Every now and then there were boys with whom I got along well, but not very often. „

I talk to him about his shyness, which he mentioned at the beginning, and ask him if it is something that has always accompanied him. „Yes, it has always been like that. I’m also always afraid to talk to people. It’s quite bad,“ he laughs softly. „I need a reason to speak to someone. So I don’t talk to anyone in the club or anything. It’s really bad.“ He continues: „If for example I’m going to meet people at a party now, that’s for me – I can’t do that at all. That’s always a topic in my therapy, how I can get rid of that, but I haven’t managed it yet.“ I ask him what strategies he has already learned to do this. „So at the end of the day, my therapist says you have to bear that feeling of rejection. You have to go through it, through this fear. But you just have to repeat it so many times until it becomes less.“ He says: „I was at the club with two friends the other day and I stood there for two hours and got upset that I didn’t dare approach anyone.“ – „But does it happen to you the other way around, that someone approaches you?“ – „Nope,“ he pauses for a moment, then corrects himself, „So now I’m saying ‚Nope‘ again, my therapist would have said, ‚What?!‘ Yes, someone approached me once, but he wasn’t my type, so it doesn’t do me any good either“, we both laugh. I ask him if he is already seeing small developments along the way. „Yep.“ He is silent for a moment. Many things are still difficult for him, he says, but sometimes he dares to make small attempts. „On the street the other day, two people passed by, I said ‚Hi!‘, they said ‚Hi!‘ too. That’s what I did, for example. I once slipped someone my number, which I would never have dared to do. That’s about it.“

I turn the page; the next picture shows the foyer of a youth hostel. Here, X attended an introductory seminar by the Begabtenförderungswerk, which supports him with a scholarship. In addition to the monthly financial support, his scholarship provider also offers political seminars, language academies abroad or project funding – things that X generally finds interesting. So far, however, he hasn’t taken advantage of them because he doesn’t have that much time, he says. Besides the university, his various social contacts, and the groups he is active in, X is also involved in university politics. After meeting some members of the Green university group at a protest, he has been part of the student parliament since last winter. He sits on the hardship committee and votes on hardship applications – by now they meet in person again. There are significantly more people at the student parliament meetings than at the committee meetings. Here, too, he is confronted with his shyness and fears. „So in the StuPa meetings I don’t dare to speak, honestly. Not until today. I’m actually rather superfluous, I think, I always just vote. But I don’t dare to talk.“ Are there things he would like to do in his life, but doesn’t do for these reasons? He thinks about it for a long time. „Well … I would like to be a politician,“ he laughs. „But I wouldn’t dare to do that. So I would have to go through this whole jungle, and I just can’t do that.“ I ask what issues are important to him politically. „LGBT issues and social democratic issues, especially concerning money. That’s important to me.“ – „Do you know where that comes from, that the issue is important to you?“, I ask. „So LGBT is obvious, I guess. The rest is like – well, when I came to Germany, I always got Bafög. In Tunisia there’s nothing like that. And financial matters somehow interest me thoroughly. And I’m someone who questions everything. I question how health insurance companies bill, I question how a student loan application is calculated, I’ve also read through the law. And I just find that somehow exciting.“ – „And is it more the systemic part that interests you, or also injustices or something like that?“ – „Both!“ We talk about which party he feels close to. „I’m thinking of switching to the SPD university group, because the Greens aren’t really my thing, because I love planes. I’m an absolute fan of planes. And I love to fly.“ – „That’s the main point?“ – „Yeah, and … of the things that are important to me that I mentioned to you, I didn’t mention environment. Because I mean, I can’t take care of everything. Environmental issues are not my – it just doesn’t interest me.“ By now it has become hot, although we are sitting in the shade. The woman on our left has long since left, as have the young men.

I put the next picture between us: it shows the university cafeteria. After classes, X is often here with his fellow students, eating, chatting. „Do you like going to university?“ I ask him. „Yes, I love studying. I also like being in the lecture hall and stuff. Yeah, it’s fun.“ The next photo shows the lecture hall. „That’s actually my favourite,“ X says. „That was empirical economics, that was my favourite subject this semester.“ I ask if he already knows what he wants to do after his Bachelor’s degree. Definitely a Master’s, but he doesn’t know which one yet. When he is finished with his studies, X would like to move away from the Ruhr area. „I don’t know, the Ruhr area – as I said, it sounds racist, but it’s so homophobic. Well, I just don’t feel comfortable. I can’t help how I feel.“ He continues: „Big cities like Berlin or Cologne are not always the best, because there are also corners that are a bit homophobic. But cities like Tübingen, or Lake Constance or Kiel or I don’t know…“ – “So the most important thing for you is that you can feel safe there,“ I ask. „Yes, that would be most important to me. And I also have to see where I fit in professionally. Where I can find a company where I can work.“

We continue to browse through the photos. A picture from the train: „I like travelling by train, that’s why I photographed station stuff like this.“ Another station photo: „I’m very often at stations.” X travels a lot, often meeting up with his friends in other cities. The next picture shows the house where his grandmother lives, in a village on the Dutch border, in the area where his mother originally comes from. „I like these villages, I think they are beautiful. Really German.“ About every two months, he is here, visiting his grandma. Even when he lived in Tunisia, they had regular contact. „Always telephone, telephone, telephone. Visiting was more like every few years.“ She visited Tunisia twice. „Were you actually in Germany during that time?“ I ask. „I moved to Tunisia in 2008. Until 2010, I was still in Germany twice a year, so it didn’t feel like I was living there yet, because I was still here so often, because my mum only came in 2010. Then I went to Germany once in 2010 and then again in 2015. Because my parents were always broke, they couldn’t manage it. Then in 2017 I was in Germany twice. And then I moved here.“ I ask him what it was like living alone with his father in Tunisia at first. „I missed my mum a lot and cried. Dad, typical Tunisian: ‚Yeah, don’t be like that, be a man‘ and stuff. Well, he didn’t actively say that, but I knew that was his attitude. Otherwise, it was actually okay.“ I ask why his father and he went ahead alone, without the mother. „Because my mum was also still working and dad – we had built a house in Tunisia – dad was supervising it and stuff. Mum was still working.“ His mother – like X now – studied economics and worked in that field at the time. In Tunisia she worked as a language teacher. „What did your dad do for a living?“ – „He did this and that – he used to have a café, he had taxis, he didn’t drive himself. Yes, that’s what he did.“ I ask X if he found it difficult how his parents lived and worked. „Yes, I perceived it as unstable.“ – „Did that stress you out as a child?“ He’s thinking. „Nah, not as a child. More as a teenager, because you notice it more.“ Concerning his own life, he feels he’s in control over it, he feels he is more structured. „I like to know what’s going to happen in the future.“

I keep turning the photos. The next picture was taken at the station where his grandmother drops him off when he goes back to the Ruhr area. „I find it idyllic. I like those houses, I like the silence there. But I still wouldn’t move there.“ The house they lived in back in Tunisia has long been owned by others. „We used to buy and sell houses, buy and sell. “ I ask X if he can quickly feel at home in new places. „It depends a lot on whether I meet people who live in that place or not,“ he explains. „If I die lonely in my room, that doesn’t help me, no matter how nice it is.“

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar